Alison McDonald is the Chief Creative Officer at Gagosian and has overseen marketing and publications at the gallery since 2002. During her tenure she has worked closely with Larry Gagosian to shape every aspect of the gallery’s extensive publishing program and has personally overseen more than five hundred books dedicated to the gallery’s artists. In 2020, McDonald was included in the Observer’s Arts Power 50.

Alison McDonaldIt seems we may have had a mutual friend in Richard Marshall. I knew him toward the end of his career, when he was an independent curator and overseeing programming for Lever House, but you worked closely with him when you were both relatively early in your careers, having graduated from the Whitney Independent Study Program. What was that moment like?

Richard ArmstrongThe Whitney Independent Study Program opened many doors for me in the 1970s. Not only did I get to know artists of my generation, but I also learned how one works in a museum alongside aspiring curators, such as the late Richard Marshall. Curator Marcia Tucker became a kind of mentor, hiring me to help her with the 1975 Whitney Biennial as well as the Al Held retrospective she did in 1974. She had already put me in touch with Held and with Nancy Graves, and I acted as a part-time secretary for both of them. Experiencing the working life of a New York artist was eye-opening and introduced me to two generations of artists who were their friends and contemporaries. Both lived and maintained studios on West Broadway, downtown’s Main Street for art. Marcia urged me to take a job as curator at the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art [now the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego], which I did. I met and befriended many California artists, north and south, as well as other museum curators and collectors.

AMCDWhat were some highlights from the time you spent at the Whitney as a curator? During that same moment you also worked closely with Thelma Golden and Lisa Phillips. The three of you went on to be directors at prominent New York museums. Have you stayed in touch with these early colleagues?

RAAfter four years I returned to New York and the Whitney—first working with art history students in the ISP, then as a curator. The 1980s, under Tom Armstrong’s leadership, saw the museum turn from its long allegiance with artists of the Whitney Studio Club into a forward-looking and -collecting institution that was more in touch with the art of the time. Armstrong encouraged his young staff to perform, and the museum’s collection and exhibition schedule changed. My colleagues, who were also early in their careers, such as Barbara Haskell, Patterson Sims, Jennifer Russell, Richard Marshall, Lisa Phillips, Thelma Golden, and, somewhat later, Adam Weinberg, became lifelong friends.

AMCDWhy did you move to Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh? What intrigued you about that opportunity? During your time there, you started as a curator and ultimately became the director of the museum. What do you see as the fundamental differences between your work as a curator and as a director?

RAAfter Tom Armstrong’s dismissal from the Whitney, I became disaffected by the museum’s leadership and accepted a curatorial position at Carnegie Museum of Art, organizing the 1995 Carnegie International in its centenary edition. At its close in 1996 I imagined beginning to work on the next International when the museum’s director resigned. Partly in self-defense and partly because my curatorial ideas were few, I sought the role and became director. Personal experience had shown me that active and productive curators were the lifeblood of any museum, and recalling the support of Armstrong, I allied myself with the Carnegie curators in what became a period of great growth for that museum. Even today, in much-changed social circumstances, directors are only as good as their curators.

AMCDWhat brought you back to New York?

RAAfter more than fifteen years in Pittsburgh, I decided moving back to New York was obligatory, and I returned, jobless. The Guggenheim position appeared unexpectedly, and quickly became a great challenge and a magnification—geographically and intellectually—of any previous role.

AMCDYou spent fourteen years overseeing the Guggenheim. What were some of the goals you had when you started that position? How did things change there during your tenure?

RAComing to the Guggenheim was the third time a large door opened to me. First, at the Whitney, in getting to know artists across the country; second, at the Carnegie, where organizing the 1995 International meant I traveled extensively, seeing artists worldwide (or what I naïvely thought was worldwide); and finally, at the Guggenheim, where sister institutions in Venice and Bilbao meant frequent contact at each place as well as launching the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi—a part of the world I hardly knew. Beyond which, the museum was well into its Asian Art Initiative, obliging consistent travels to that huge part of the planet. Getting to know artists and colleagues truly across the globe was a central asset of the directorship. The curators and I worked hard to make certain a wide range of artists’ work from all parts of the world was exhibited and acquired.

Two wider social phenomena have washed over the museum: the internet, with its instant access to data and, perhaps even more importantly, access to imagery; and the recognition that a wider array of artists and practices exist and deserve attention.

Richard Armstrong

AMcdWhat do you feel are some of the biggest challenges that museums are facing at this moment?

RAInternal and external expectations of art museums have changed significantly during my fifty years working first as a curator, then as a director. Whereas previously working in a museum was seen to be a kind of privilege, and it was not well-paid work, today’s staff participates more in decisions and wants more equitable pay. Neither is unreasonable, but accommodating those requests can be a challenge that is unprecedented in an institution’s history. At the same time audiences have higher expectations: an ease of visit, more information that is more participatory, and in some places, an emphasis on identity as a crucial factor in what is being shown and even how it is being shown. Two wider social phenomena have washed over the museum: the internet, with its instant access to data and, perhaps even more importantly, access to imagery; and the recognition that a wider array of artists and practices exist and deserve attention.

In my early years at the Whitney, decisions were mostly closed, very much like the process at the Carnegie. Over the past decade or so, during my Guggenheim years, the board recognized its homogeneity and sought to correct that, and the staff pushed for more variety in our programming and acquisitions. We had already assumed greater geographic responsibilities—the reality of claiming to be a global institution—and gender, race, and sexual orientation rose up as determining factors. This year’s Venice Biennale demonstrates the worldwide appeal of this more inclusive approach. Directors and curators live in a heatedly politicized society, and their decisions now reflect that.

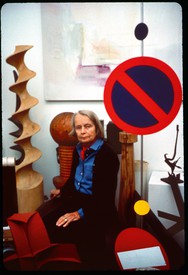

AMCDCongratulations on joining the board of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation. Did you know her while she was alive?

RAI first met Helen Frankenthaler in 1974 while I was a Helena Rubinstein Fellow in the Whitney’s Independent Study Program. In those early days of the program, fellows organized and presented shows in the museum—then located in the Breuer building on Madison Avenue. I collaborated with a small group of colleagues to organize the show Frank O’Hara: A Poet Among Painters. O’Hara’s poems were juxtaposed with works from the Whitney collection, including a large painting by Frankenthaler, Flood [1967]. She somehow got wind of it and appeared the day before the opening for a look. She seemed pleased, and I recall her smiling at me from the ladder I was standing on. A good beginning.

AMCDIf I am not mistaken, your wife, Dorsey Waxter, worked at the André Emmerich Gallery until 1991. That was Frankenthaler’s longtime gallerist. Were she and Helen close?

RAYes, she knew and liked Frankenthaler, and because her parents had the foresight to acquire a fascinating painting on paper from the 1980s, I am privileged to live with a piece of her artwork and see it every day. Its subject is endlessly baffling—a tabletop still life or a thoroughly abstract composition? Either and both are engaging.

Remarkably, Frankenthaler was able to sustain and expand her invention until late in her life, and served as an inspiration to more than one generation of artists who followed her. Unquestionably, she was one of the titans of twentieth-century painting.

Richard Armstrong

AMCDThe Guggenheim in New York hosted three solo exhibitions on Helen Frankenthaler: a show of ceramic tiles in 1975, an exhibition dedicated to her works on paper in 1985, and a show titled After Mountains and Sea in 1998. You were not the director at the time, but I wonder if you saw those exhibitions and if you could reflect on your impression of the shows?

RAYes, I recall having seen the painted tile show at the Guggenheim, and of course I was familiar with her work in the Whitney and Guggenheim collections as well as having seen shows at the André Emmerich Gallery and elsewhere. I was so impressed with her later prints that I had overseen the Carnegie acquisition of Madame Butterfly [2000]. Another work of hers, The Facade [1954], which was in the museum’s collection, shows a concentration of artistic energies that I found stimulating, and I frequently hung it near a work by David Smith, Question and Answer [1951], that seemed a three-dimensional counterpart to her work. Of course I knew of their friendship and shared connection with Bennington.

AMCDYou curated a group show at the Guggenheim in 2010, Color Fields, that included Frankenthaler’s work. Would you talk a bit about the premise of that show?

RAAbstract Expressionism and its immediate successors remained my visual touchstones. When the opportunity arose to organize a small exhibition for the Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, in 2010, I had picked some examples of works from the Guggenheim collection, calling it Color Fields, expanding the category and of course featuring Frankenthaler’s work.

AMCDWhat do you feel were some of Frankenthaler’s most notable contributions to art history or the art of her time? Do you feel she faced challenges that other artists of her generation did not?

RABesides a unique gestural touch and her unmatched color sense, Frankenthaler’s taste for large scale distinguished her work from an early moment. It might be called her fearlessness. She enjoyed support from many of the noted figures of the first generation of Abstract Expressionists as well as their principal theoretician, Clement Greenberg, but Frankenthaler forged her own path in multiple media. Her works on paper—many prints and drawings—often condense and exploit the visual acuity of her larger paintings. Remarkably, she was able to sustain and expand her invention until late in her life and served as an inspiration to more than one generation of artists who followed her. Unquestionably, she was one of the titans of twentieth-century painting.

AMCDThe Helen Frankenthaler Foundation has contributed more than $45 million in direct grants and $30 million in gifts of paintings or other artworks to museums globally. They have also been working for several years on research that will ultimately become a catalogue raisonné on the artist’s work. What thoughts do you have on the work they have done to date and on what lies ahead for Frankenthaler’s legacy?

RAWhen Lise Motherwell and Michael Hecht broached the idea of my joining the board of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, I was flattered and quite keen to agree. I knew of its timely and empathetic grants during the COVID crisis, as well as its progressive leadership helping institutions analyze and act on energy-consumption change under its chair at the time, Clifford Ross. As an applicant to the foundation while at the Guggenheim, I was impressed by its willingness to listen to the needs of museums.

Further, I have known the executive director, Elizabeth Smith, for decades and have long admired her work as a curator and now as leader of the foundation. It is an important moment for the foundation, with Frankenthaler shows in the United States and elsewhere in discussion, and I certainly look forward to their completion of the all-important catalogue raisonné.

AMCDWould you be able to share a personal remembrance from time you spent with Frankenthaler?

RAWorking for Al Held, a strict if streetwise formalist, offered many opportunities to hear about the heyday of the 9th Street artists of the 1950s. Held also introduced me to Irving Sandler, the era’s most gifted chronicler, whom I admired. All the marquee names featured in their animated conversations, including Helen Frankenthaler. As she and Held shared the Emmerich Gallery as a dealer, they were friends. I recall one day when she was meant to visit his studio, and I was dispatched to get club soda as refreshment. I was surprised when she asked if it was salt-free club soda, as I was unaware of the nuances of the drink. That discernment tickled me and reminded me of her reputation for perfection.